In Part 2 of this article series on B2B fraud, we described the first two layers within a comprehensive business fraud risk assessment framework: 1) verifying business identity, and 2) uncovering risks behind a device, IP, or email address. In this final article of the series, we look at a third key layer: evaluating a company’s operating status and financial profile, which can provide clues regarding potential fraud risk. We conclude by discussing the benefits of participating in consortiums that share data about known fraud schemes and threats.

Third layer: evaluating operational and financial factors

Although it can be challenging to differentiate first-party fraud risk from more typical credit risk, both during the application process and after onboarding, the key distinction is intent — active use of deception to obtain goods and services for financial benefit with no intent to pay. When evaluating fraud risk, the financial incentives for the potential first-party fraudster are important considerations.

As an example, a company may be consistently making payments on time and is considered a low credit risk. But then the company starts maxing out its credit line and eventually defaults on all its payments. This is typical “bust-out” behavior (see Part 1 of this series, “Types of Digital Fraud”). It demonstrates a fraudster’s level of skill and patience in gaming the system. When activity like this comes to light, it should trigger an examination of the financial health of the business or vendor you are dealing with and closer scrutiny of its transactional behaviors over time.

Key questions to ask during the fraud assessment process include:

- Is the business making more credit inquiries than usual? Has it started spending to the limit of its credit line?

- Is the business making timely payments?

- Is the company trending up or down on key financial metrics?

- Is it already delinquent or on the brink of bankruptcy?

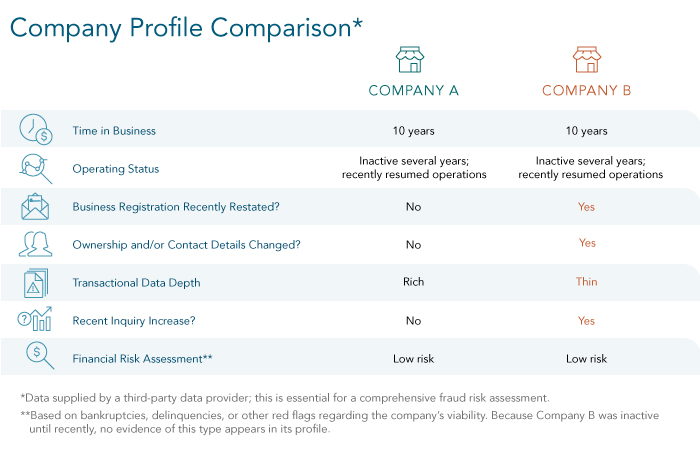

Establishing a brand-new business requires a significant amount of effort. In contrast, leveraging an existing business shell to commit fraud is much simpler. In the table below, the highlighted aspects of Company B’s profile would indicate that this company presents a higher fraud risk than Company A:

Fraud data consortiums: an anti-fraud best practice

Efforts to fight fraud are far more effective when they’re conducted by a group rather than by individual companies. This understanding has led to the creation of consortiums that exist to share data and information about known fraudulent activity and the actors behind it. Consortiums for fraud prevention facilitate close collaboration among companies to pool their knowledge of suspicious or confirmed fraud events.

These consortiums give their members access to richer data, analytics, and intelligence about past fraud attempts. This data typically includes three major “buckets” of intelligence: OSINT (Open Source Intelligence), SIGINT (Signals Intelligence), and HUMINT (Human Intelligence).

- OSINT is intelligence found in the public domain, such as news reports, online databases, public records, videos, or social media.

- SIGINT is internal, proprietary intelligence on the commercial activity of a business.

- HUMINT is intelligence obtained from human sources, such as business owners, landlords, neighboring businesses, and sometimes law enforcement, through active investigation and interviews.

Armed with this information, companies can reinforce their fraud detection efforts, since fraudsters often leverage similar tactics and data to pursue their activities within the same lines of businesses or across industries. Fraud consortium databases can effectively create “industry negative lists” that give advance notice to other consortium members about individuals or entities they should not do business with.

A few years ago, it wasn’t typical for organizations to be members of such consortiums. But the global pandemic — which triggered a significant increase in instances of commercial fraud, as businesses shifted to digital storefronts and remote work — changed that dramatically. Since 2020, there has been a notable uptick in the number of organizations actively participating in fraud data consortiums, giving and receiving data and intelligence to help further the larger effort to detect and prevent B2B fraud.1

Over the course of our three articles on B2B fraud, our goal has been to help you understand the most common types of commercial fraud and the elements of a basic framework for detecting and assessing fraud risk. To learn more about the current fraud landscape and effective data-driven strategies for protecting your business, watch our recent webcast, “Best Practices in Today’s Fight Against Fraud”.

Previous Articles in Our Series — Financial Fraud: What You Need to Know to Protect Your Business

Part 1 — Types of Digital Fraud: You Can’t Fight What You Don’t Understand

Part 2 — How to Frustrate Fraudsters Before They Cause Damage

1 Simon Marchand, “New Fraud Risks for Telcos — and How to Handle Them,” Communications Fraud Control Association (CFCA.org), 27 April 2021.

The information provided in articles and blog posts are suggestions only, based on best practices, and provided as-is. Dun & Bradstreet is not liable for the outcome or results of specific programs or tactics. Please contact an attorney or tax professional if you are in need of legal or financial advice.