Brexit Could Hit Investment, Trade, Aid, and Integration in Latin America, But There Will Also Be Opportunities

Originally published in the London School of Economics and Political Science Journal

The ramifications of the UK’s decision to leave the European Union for Latin America remain unclear eight months after the Brexit referendum. Indeed, the uncertainty that seems to pervade all things Brexit is likely to continue for the next couple of years as the UK and EU negotiate the terms of their divorce. Having said that, we could reasonably assume that the repercussions of the UK-EU split will be transmitted to Latin America primarily via four channels – foreign direct investment (FDI), trade, development funding, and political influence.

Foreign Direct Investment

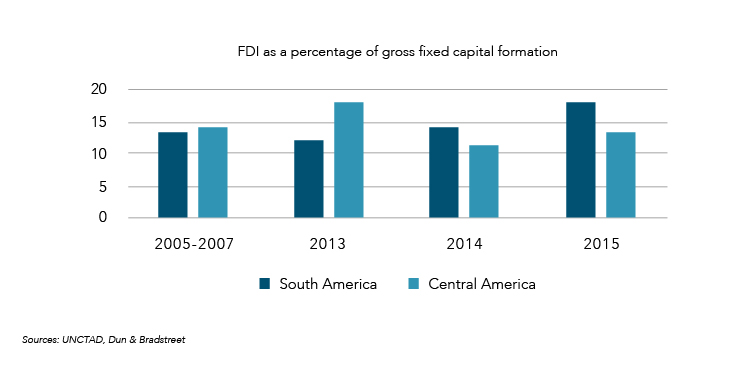

FDI has played a notable role in the expansion of traditional and non-traditional sectors in the region such as mining, telecommunications, banking, and renewable energy. Today the EU is Latin America’s largest investor with FDI stock of roughly €500 billion, equal to 43 per cent of regional stocks; Spain, the UK, Belgium, France, the Netherlands, and Germany are among the top 10 investor economies as ranked by UNCTAD. Unsurprisingly, the share of investment flows to the extractive sector has been on the decline now that the ‘commodity super-cycle’ is over. Conversely, the region’s services sector is receiving a larger share of inflows; in Central America the sector accounts for around 65 per cent of inward FDI. Compared with the EU, the UK’s role as an investor in Latin America is considerably smaller and heavily skewed to the natural resource sector in a few economies. In 2015 net UK FDI to Central America was €3 billion, and at the country level the UK accounts for 18 per cent of Peru’s inward FDI and is Colombia’s second largest investor economy.

How then could Brexit affect FDI flows to Latin America? Prime Minister Theresa May’s determination to control immigration and remove the UK from the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice means that the UK will likely leave the Single Market. Once Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty is invoked, the heightened uncertainty surrounding the ensuing negotiations could dampen growth in both the UK and the EU and depress outward FDI flows. In addition to the balance of payment impacts, narrower investment flows could hamper the region’s economic diversification efforts which are now crucial for sustainable growth in the post-commodity boom years. From the UK’s standpoint, a weaker pound sterling and heightened business uncertainty would lead to lower flows to economies that now receive UK investment. But on a more positive note, Brexit could provide an opportunity to craft modern bilateral investment treaties between the United Kingdom and regional economies.

Trade

The EU is Latin America’s second largest trading partner (after the US), with this relationship underpinned by trade agreements with Mexico, Chile, Peru and Colombia, as well as the Central American grouping SICA. Today, over 70 per cent of Latin America’s exports to Europe are from the primary sector. In contrast, Latin America’s trade with the UK is quite small at less than 1 per cent of regional exports. At this time, it is fair to assume that the EU-27’s trade policy vis-à-vis Latin America will remain broadly unchanged. However, if Brexit triggers a significant fall in EU demand for exports, deterioration in both external and fiscal accounts is probable. While the aforementioned EU trade agreements would no longer include the UK after it leaves the European Union, Brexit will again create room for the formulation of more up-to-date and mutually-beneficial trade agreements between the UK and Latin America, particularly as the UK would no longer be restricted by EU trade rules. That said, at present the UK’s trade negotiation expertise and capacity is extremely limited.

Development Aid

The European Union is an important source of development funding for Latin America with ties that date back to the early 1990s. The EU has allocated €925 million to its Latin American regional development programme for the period 2014 to 2020, and dependence on these funds in Latin America varies by country and sub-region. Comprising loans, grants and other funding mechanisms, the scope of EU development aid funding has widened from higher education and SME support to include sustainable development, climate change, governance, disaster management, and environmental sustainability amongst others. The UK’s withdrawal from the EU would result in a loss of around £6 billion in annual contributions to the EU’s foreign policy and international development programme. While development aid to the region is expected to continue post-Brexit, a review of existing mechanisms for funding disbursement would probably be required to ensure vulnerable recipient-economies continue to benefit from the smaller pool of funding.

Politics

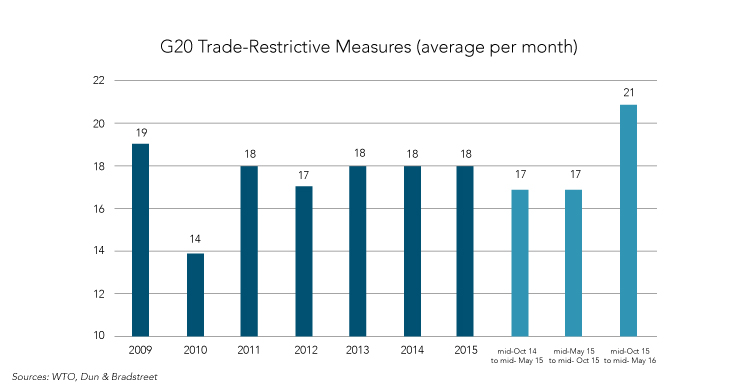

A new global risk that is gaining momentum is “deglobalisation.” That is, growing discontent with globalisation amongst sizeable sections of the world’s population. This is most clearly visible in the rise of populist movements in western economies and the emergence of leaders who propose greater protectionism and are less well disposed towards free trade as it exists today. Barriers to trade are already increasing (as shown below).

With the Brexit process scheduled to start this quarter and Donald Trump’s ultra-protectionist stance creating ripples throughout the global economy, the forces of deglobalisation can be expected to become stronger in the medium term. It is not inconceivable to think that Latin America’s voters could gravitate to politicians of a similar bent in response to real or anticipated threats from some of their key trade and investment partners.

What is the Impact on Latin America Post-Brexit?

While it is difficult to quantify the ultimate impact of Brexit on Latin America at this time, the region has a number of options to minimise negative fallout. For instance, it could aggressively pursue deeper trade, investment and financial links with other extra-regional economies such as China and India. In fact, it appears that momentum is building in this direction. At October’s BRICS meeting, members agreed to increase trade amongst themselves to $500 billion over the coming years, whereas India and Brazil have agreed to push for an expansion of the existing India-Mercosur Preferential Trade Agreement.

For the region, Brexit highlights the need for renewed urgency in the push for deeper regional integration, structural reform, and the revision of existing models of economic growth and development. If Latin America is to grow sustainably and thrive after the dust of Brexit settles, new approaches will be required to lift productivity, reduce inequality, drive economic diversification, encourage innovation, and build an appropriately skilled workforce at the same time as sharpening international competitiveness. One of the core lessons of Brexit for the Latin American region, which can boast success in lifting millions out of poverty in past two decades, is that leaders must recognise the concerns of those who feel they have been left behind, despite what the data might appear to tell us.